‘The astonishing survival of the human spirit’: Jenny Mitchell's poetry on the history of enslavement

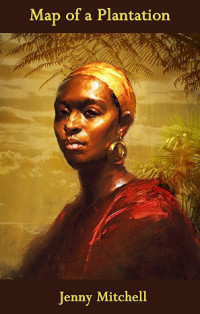

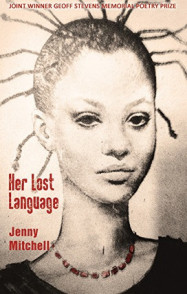

Jenny Mitchell’s prizewinning debut collection Her Lost Language was an exploration of the impact of British transatlantic enslavement on black lives and family dynamics. Her new collection Map of a Plantation gives voice to different characters on a Jamaican cane plantation. In an interview with Write Loud Loud, Jenny Mitchell talks about her research, including archival records of slave auctions; a history of “enormous violence and oppression, but also of constant resistance and the astonishing survival of the human spirit”; and the possibility of healing.

In one sense your new poetry collection, Map of a Plantation, can be read as a crucial history lesson, delivering facts about slavery and colonialism that British people have been deprived of for so many years. (On a brief holiday in the Caribbean several years ago, I was ashamed and shocked at how little I knew). Would you agree with that? Was that one of your intentions?

I really want to write poetry that people can engage with on an emotional and intellectual level. Any ‘lessons’ that come out of that are great but it feels natural to write about a history that often gets buried or obscured.

It’s really important to me that the legacies of enslavement be widely known because this may be the only way they can be healed. It’s an emotive subject, almost unbearably so, but I think this might be the time when people want to face the history. Otherwise, will we keep going backwards into a primitive idea of racial difference and separation, with out-dated talk of ‘black communities’ (meaning ghettoes) and ‘middle England’ (meaning affluent white people)?

I began the research because it seemed as if I constantly had to explain and justify my presence in this country despite it being my homeland. I read more books on enslavement than I can remember and studied archival records of slave auctions online. Then I began to run creative projects for young people and teachers in museums which meant I could get to know the objects relating to the history.

I learnt that it was one of enormous violence and oppression, but also of constant resistance and the astonishing survival of the human spirit. I also learnt that abolition was not something ‘gifted’ to black people by good white men like Wilberforce. It was a hard-won battle with constant black-led uprisings in the Caribbean.

Most importantly on a personal level, I realised I had every right to call Britain home. My ancestors had suffered hundreds of years of state-sanctioned violence. They helped to build this nation from the ground up and had reaped structural racism as a ‘reward’.

I gained a real grounding and an enormous amount of confidence by learning so much. I think one of the reasons why the history is generally absent, and now being denied by the Sewell report, is that if it was known in full there would be widespread demands for reparations. The cost to the state for all of that unpaid labour is unimaginable.

It would also be impossible to suggest that enslavement is Black history. White people would no longer be present as kindly abolitionists but would have to stand front and centre as enslavers. I wonder what would happen to the ‘comfortable’ idea of white privilege if it was seen as being built on unspeakable suffering?

The subject matter of your collection has involved two sides taking diametrically opposite views about revising our view of Britain’s colonial history. Do you have strong feelings about that yourself?

I think the views are opposite only in that one seeks to whitewash the past and the other seeks to uncover it. I hope I have more in common with the latter.

I think it’s no accident that the Sewell report is meant to be a response to the Black Lives Matter initiatives that took to the streets in 2020. The report seems to deny that there is any need for the movement in the first place. That feels like a fearful response and one that has been widely dismissed for good reason.

Following on, one of the reasons why I wrote my collection is that during the workshops in museums, I realised there was a lot of shame around the history. For young black people it often felt as if they were angry that their ancestors had passively allowed themselves to be enslaved. My memory of the young white people is that they were unable to articulate any sort of feelings other than a form of guilt and shame themselves. The teachers also seemed to struggle on an emotional level to look at the history.

It felt incredibly important to me to show that enslaved people were in a constant battle against their barbaric treatment, hence the need for chains and violent oppression. But I also wanted to talk about common humanity and the possibility of healing.

I think writing novels gives something that poetry doesn’t. I needed to spend years working alone, for the most part, as a way of processing the research into enslavement. It forms the basis of my two novels and was perhaps necessary as a way of filtering out what I did and did not need to put in my debut collection, Her Lost Language, and then into Map of a Plantation.

There’s a great community of poets in this country and now that it’s impossible to perform live I get a huge amount from sharing work and information on Twitter.

Poetry seems to offer so many opportunities for bonding, as well as space for disagreement and controversy. I just want my work to be part of the conversation and hopefully part of a change.

Many thanks to Greg Freeman and Write Out Loud for the opportunity to take part in this interview.

Jenny Mitchell is winner of the Folklore prize 2020, the Segora prize 2020, the Aryamati prize 2020, the Fosseway prize 2020, a Bread and Roses award and Joint Winner of the Geoff Stevens Memorial Prize. She has been nominated for the Forward prize: Best Single Poem, and her best-selling debut collection, Her Lost Language, is one of 44 Poetry Books for 2019 (Poetry Wales), and a Jhalak Prize #bookwelove recommendation. Her poems have also been published in Magma, The Rialto, The Morning Star, and The New European among others, as well as in several anthologies. She has performed her work in Italy, France and regularly in London.

Jenny Mitchell, Map of a Plantation, Indigo Dreams

Jenny Mitchell, Her Lost Language, Indigo Dreams

Background: ‘Still struggling after all these years:’ Jenny Mitchell’s article in the Morning Star

Background: Greg Freeman's review of 'Map of a Plantation'

PHOTOGRAPH: BILLY GRANT