Dissenter, mariner, spy, journalist, poet: the remarkable life of Basil Bunting

Born in Scotswood, Newcastle in 1900, he was a conscientious objector in the first world war, and was given hard labour in Wormwood Scrubs and other jails. In the 1930s he became a close friend of Ezra Pound, before being alienated by the latter’s anti-semitism. For two years he skippered a millionaire’s yacht, despite poor eyesight. In the second world war, despite his eyesight he managed to join the RAF, and by 1945 had become a squadron leader, and a vice-consul. After the war he was chief of political intelligence in Tehran, as well as being a Times correspondent, once joining in with an angry mob shouting ‘Death to Bunting!’ outside a journalists’ hotel. He was sacked from his British government job for marrying a 14-year-old girl – his second wife - when he was in his late 40s, although he remained a correspondent of the Times for a while. There’s much more, but that’s enough to absorb for now …

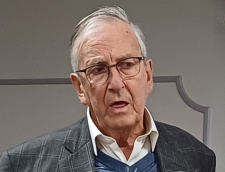

‘Basil Bunting – the most significant Northumbrian writer since Bede?’ – was a talk given at Berwick literary festival by former college lecturer Mike Fraser, who described himself as “an amateur biographer, rather than a poetry expert”, and keen that Bunting should be better known. There were two important contributions, one from a former newspaper colleague of Bunting’s at Newcastle’s Evening Chronicle in the early 1960s, and the other from poetry editor Neil Astley, who set up his Bloodaxe publishing company in 1978, a year after hearing Bunting read his long and celebrated poem ‘Briggflatts’.

There he met American poets such as Allen Ginsberg , who he nagged to compress his work. And after years of discouragement he was enthused and inspired to write ‘Briggflatts’, some of it on the train between Newcastle and Wylam – a 700-line poem that among other things, celebrates love and mourns its loss. Mike Fraser told the Berwick audience that ‘Briggflatts’ caused a literary sensation in the mid-60s, and was regarded in some quarters as the biggest poetry event in England since publication of TS Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’. Ginsberg himself conceded that Bunting was “the best poet alive, of the old folks”.

Mike Fraser said that the story behind ‘Briggflatts’ was of an unrequited love that Bunting still felt for a young girl, Peggy Greenbank, that he had met at a Cumbrian Quaker hamlet when she was eight, and he 13. Their relationship was severed as a result of an unanswered letter when Bunting was still in his teens. And that would have been that … until he wrote ‘Briggflatts’, tracked the now-married Peggy down, and met her occasionally at weekends for a few years, with the knowledge of his own wife, but not of Peggy’s husband. Mike Fraser said Bunting described these encounters as generating “great happiness such as I’ve never known since I was a child”.

By this time he had given up the Chronicle job, and was now taking up lectureships and academic appointments in both the US and UK. However, in the 1970s his wife threw him out during a snowstorm, and from then on he led a fairly nomadic existence in the north-east before his death after a short illness in 1985.

He had many strong views. He was a proud Northumbrian, describing Geordie as a “bastard language”, and apparently hated southerners, partly because of the way they pronounced the word ‘water.’ Bunting preferred it to sound like ‘watter’.

He also said: “Poetry, like music, is to be heard … poetry lies dead on the page, until some voice brings it to life.” The Berwick audience heard the poet reading from ‘Briggflatts’ in distinctive, declaratory tones. Neil Astley conceded that there was “exaggeration in the enunciation” but said of critics who described Bunting’s delivery as artificial and mannered, “they don’t actually know the Northumbrian voice”. He concluded: “Like Pound, he is a Modernist poet who doesn’t have a modernist audience. The vast proportion of Modernist poetry doesn’t have much public following either.” As if to bear this out, two members of the packed Berwick audience were overheard as they walked away afterwards: “Had you heard of him before this? No? Me, neither.”

MAIN PHOTOGRAPH: BLOODAXE BOOKS

Rodney Wood

Sat 28th Oct 2023 18:29

Very nice thanks Greg. But let's not forget the close relationship with music in the poem.