Chemistry, poetry, and laughing gas: analysing the verses of Sir Humphry Davy

In 1799 - the year that Napoleon gained power in France – the chemist Sir Humphry Davy, at the age of 21, discovered the physiological effect of nitrous oxide, or laughing gas. Being Davy, he wrote a poem about it:

Not in the ideal dreams of wild desire

Have I beheld a rapture wakening form

My bosom burns with no unhallowed fire

Yet is my cheek with rosy blushes warm

Yet are my eyes with sparkling lustre filled

Yet is my mouth implete with murmuring sound

Yet are my limbs with inward transport thrill’d

And clad with new born mightiness round -

(‘On Breathing the Nitrous Oxide’)

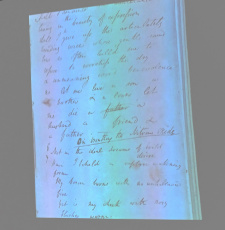

The notebooks are held in the Royal Institution in London. But via the benefits of digital technology, nearly 11,500 pages have already been transcribed by researchers and volunteers from all over the world. The project is still looking for more volunteers to help carry on the work. There are many more notebooks that still need to be transcribed.

Sharon pointed out that Davy isolated potassium, identified sodium, and by her reckoning isolated more chemical elements than anyone else. Working with his assistant Michael Faraday, he developed a miners’ safety lamp after being approached to do so following a pit disaster in the north-east. You might expect his notebooks to be packed with technical details, and there are indeed plenty of those. But they also contain “scurrilous gossip about his contemporaries, as well as first-hand witness account of his discoveries”.

Davy is said to have gone to the Wye valley, where Wordsworth wrote his poem about Tintern Abbey, with a bag of nitrous oxide. Another of his poems has a distinctly Wordsworthian air. Not surprisingly, perhaps, since it was inspired by Ullswater, where William and Dorothy saw those daffodils while out walking. Davy’s poem philosophises about “a lovely landscape in its whole”:

We do not fix upon one cave or rock,

Or woody hill, out of the mighty range

Of the wide scenery, - we rather mount

A lofty knoll to mark the varied whole. –

The waters blue, the mountains grey and dim,

The shaggy hills and the embattled cliffs,

With their mysterious glens, awakening

Imaginations wild, - interminable!

Davy did not publish much of his poetry. The little he did was generally published privately, and anonymously. Yet Sharon said he was proud of his work: “He recited it at parties. That’s what they did in those days.”

Remarkable as it may seem today, Davy was always trying to gain the same public recognition for science as there was then for poetry. “He was almost competing with Wordsworth,” Sharon said. And she added that it had been very rewarding going through the hundreds of poems in the notebooks, and making discoveries, such as Coleridge suggesting changes to one, a poem that gets longer in later versions. “I love this. There is such a joy to find this out,” she said.

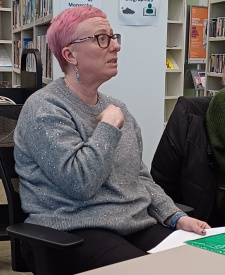

There was real joy among those taking part in the workshop at Morpeth library, too. Many of them were local poets who knew each other. But one couple had come up for the talk from Humberside – “the historic southern border of Northumbria”, as the husband put it. His wife was a retired scientist, and current poet.

Well done Sharon Ruston, and Jennifer Kinnear of Northumberland Libraries – which also runs the nearby Northern Poetry Library - for putting on such an event that prompted very lively participation and discussion. The event was staged in conjunction with Northumberland Archives, to complement the touring Davy Notebooks Exhibition, which had been on display at County Hall, Morpeth, from November to January.

Davy was born in Penzance in 1778, and died in 1829 in Switzerland, after suffering a stroke at athe age of 48.

Perhaps George Eliot should have the final word, in a passage from her wise and wonderful 19th century novel Middlemarch:

"Sir Humphry Davy?" said Mr. Brooke, over the soup, in his easy smiling way, taking up Sir James Chettam's remark that he was studying Davy's Agricultural Chemistry. "Well, now, Sir Humphry Davy; I dined with him years ago at Cartwright's, and Wordsworth was there too - the poet Wordsworth, you know. Now there was something singular. I was at Cambridge when Wordsworth was there, and I never met him - and I dined with him twenty years afterwards at Cartwright's. There's an oddity in things, now. But Davy was there: he was a poet too. Or, as I may say, Wordsworth was poet one, and Davy was poet two. That was true in every sense, you know."

In the coming months transcriptions with images of notebook pages will be appearing on Lancaster Digital Collections.

You can find out more about the Davy Notebooks project here

ILLUSTRATION: A group of poets carousing and composing verse under the influence of laughing gas. Coloured etching by R. Seymour, 1829 — Source, The Wellcome Library

Uilleam Ó Ceallaigh

Mon 15th Jan 2024 12:06

Chemist, Lecturer and Poet;

An alchemist in many senses of the word?