No mere trifle: recovery and discoveries from armchair poets at village book festival

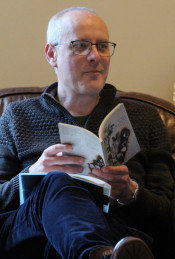

The last time I saw Richie McCaffery read was at Aldeburgh poetry festival at Snape Maltings, more than 10 years ago, with fellow up-and-coming poets such as Kim Moore. On Sunday he was reading in more intimate surroundings, sitting in an armchair in a corner of an art gallery at the Little Felton Book Festival in Northumberland, close to his home in Warkworth.

He did repeat at least one of the poems from that earlier reading, about an underground copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover that survives Dunkirk. It was from his debut pamphlet Spinning Plates. Richie was surprisingly self-deprecating about his early work, describing it as “very green and gauche”.

What had happened to him since Aldeburgh? He gave a brief history as he read more poems – a fraught relationship, a spell in Belgium and Scotland, and returning to England and Covid, and a ‘Dear John’ letter: “She left me at the height of the nesting season.” Yet he retained mixed feelings about the early months of the pandemic: “It was a time of tremendous fear, but I also felt a sense of optimism.”

Newcastle-born McCaffery concluded with a poem that mentioned “lichens awarded us like rosettes”. It was about returning to Northumberland, he said: “I’m not a true Northumbrian, but I’d like to think of myself as one.”

Ali introduced her final poem by talking about a “lovely” writers’ group in Amble, which was asked by the landlord of the pub where they meet if they might produce an anthology which he could place in guests’ bedrooms. What a great idea. Her anthology poem, she said, was about “the peace you can find in Northumberland, whether you’re lucky enough to live here, or are just visiting”. It includes lines such as “Be empty, except for dreams and stories … nourish yourself on simple chatter … so you can be your other, gently playful self”. It was a good way of summing up the warmth and humanity of her poetry.

Introducing a poem titled ‘Warehouse’, she said: “I really like industrial estates, and I really like sitting there feeling miserable. In Alnwick they knocked down my favourite warehouse to build a hotel.” She linked this penchant of hers to “why I’ve been single for so many years”, which she also referred to in a poem called ‘Lullabies’, about “my inability to have a long-term relationship”. Another poem was about “how I like to go walking on the edge of town … climbing the fence feels like coming home”.

Felton is a small, attractive village with a quiet main street and a thriving cultural atmosphere. A stranger might not guess that the A1 used to barge its way through here, and that its history as a key route between England and Scotland goes back many centuries, accumulating a number of coaching inns along the way. The gallery where the reading was held used to be the Stags Head.

Tony also read a poem about the burial of pet guinea pigs, “not grand enough for vets to raise an invoice for”, which he insisted was based on the Philip Larkin poem ‘An Arundel Tomb’.

But perhaps his tour de force was a villanelle about “walking in on your mum and dad having sex”. Its two refrains are “Never let us speak of this again” and “Just close your eyes , and count from one to ten.”

Four very different, and very accomplished poets, sitting in comfy chairs, and reading to a small but very appreciative audience on a sunny Sunday afternoon in early spring at a village book festival that was put together in a few weeks, and aimed to raise money for outdoor provision at the local primary school. We heard that the festival had already met its target to fund the groundwork. New shoots appearing …