A northern voice: accent, rhythm, and texture

Sometimes I think I like the names of the northern Dales as much as the hills and the valleys themselves. Wharfedale, Ribblesdale, Nidderdale, Swaledale, Langstrothdale, and this one, Arkengarthdale, setting for a story where a drummer boy comes out of a fellside, and out of history, playing his drum; where giants roam the valley sides, and drive herds of pigs into Richmond marketplace. Norse and Saxon place names, and the hard Norse consonants. Muker. Keld. The cold springs of adit-mined limestone valleys, gouged by glaciers and littered with erratics. Big northern skies and cold winds.

This post all stems from a conversation on a long car journey. I was speculating on whether there was such a thing as Northern Poetry or a northern poetic voice (or voices). Because it seemed to me that all the poets I gravitated towards, and whose books I bought were ‘northern’. Or, at the least, not metropolitan. When they weren’t self-evidently ‘northern’ they were ‘regional’; they came with distinct voices that could not be described as RP, and would lose something important if they were read in RP… and I guess that what they would lose would be music, rhythm, texture. The conversation in the car circled around the idea, too, that this poetry was somehow more ‘committed’, less inclined to be ironic, more inclined to wear its heart on its sleeve. I guess we knew we were teetering on the edge of a generalising sentimentality, but we were trying hard to be honest, to nail some kind of felt truth. One phrase in that conversation lodged itself in my mind. One that said that ‘metropolitan’ poetry was ‘too cool for school’, that it prided itself in its avoidance of a felt emotional engagement. I don’t know if that’s accurate or fair. But something about it resonates enough for me to want to try to pin down that elusive idea of ‘north’ and ‘northernness’.

Disraeli, Cecil and Gaskell

It’s an issue that has been bothering the English for long enough, especially in the mid -19th century, faced with the astonishing growth of the northern industrial cities. Disraeli sets the tone:

"It is the philosopher alone who can conceive of the grandeur of Manchester, and the immensity of its future."

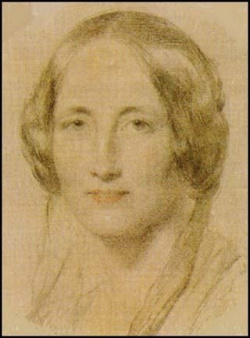

Some critics like Lord David Cecil clearly thought it was beyond the frail intellectual grasp of a woman like Mrs Gaskell, who was probably (in his mind) ill-advised to write North and South, and Mary Barton.

".... a subject … neither domestic nor pastoral … it entailed an understanding of economics and history wholly outside the range of her Victorian feminine intellect."

"After a quiet life in a country parsonage … there was something dazzling….in the energy which conquered immense difficulties with ease; the power of the machinery of Milton, the power of the men of Milton … People thronged the footpaths, most of them well dressed as regarded the material, but with a slovenly looseness which struck Margaret as different from the shabby threadbare smartness of a similar class in London."

I have always enjoyed that business of "a slovenly looseness" and the way it misses the taste, the refinement of the shabby-genteel south. And have we changed, in the last 150 years? Where do we start? Let’s start with ‘accent’. And with a quotation from Tony Harrison’s ‘Them and Uz’:

All poetry (even Cockney Keats?) you see

‘s been dubbed by [ɅS]* into RP,

Received Pronunciation please believe [ɅS]

your speech is in the hands of the Receivers

Harried for our accents

Harrison spoke for tens of thousands of us who, in the 1950s, were harried for our accents in the grammar schools we sat scholarships to get into. It would be nice to think that 60 years on we know better, but only the other day a post popped up on my Facebook page bemoaning the alleged fact of a default "poetic accent" that bedevils poetry readings. Here’s an extract:

" … the poet uses a slightly performative but mostly natural voice. It’s the voice they’d use to introduce you to their grandmother. Then they read the title of their first poem and launch into the first line. But now their voice is different. It’s as if at some point between the last breath of banter and the first breath of poem a fairy has twinkled by and dumped onto the poet’s tongue a bag of magical dust, which for some reason forces the poet to adopt a precious, lilting cadence, to end every other line on a down-note, and to introduce, pauses, within sentences, where pauses, need not go. – Whoever it is, that person has just slipped into Poet Voice, ruining everybody’s evening and their own poetry because now the audience has to spend a lot of intellectual and emotional energy trying to understand the words of the poem through a thick cloud of oratorical perfume." You can read more of this here

The article’s about American poetry readings, but I’ve heard a friend and ex-student of mine (who happens to be an actor, musician, and the voice of very many audiobooks) saying exactly the same thing about the BBC’s flagship programme Poetry Please. I don’t know whether the fact that my actor-friend is from the north is a factor in this. But I’d happily bet that it is. I think we all recognise that reverential RP poetry-accent, and run a mile when we hear it. I think we’d run equally fast from the faux-northern accent, the thick as chips ‘Yorkshire’ that still turns up in folk clubs and at poetry open mics, and is employed by them as does monologues in the Marriott Edgar tradition. Or from the faux-Mancunian accent of them as thinks they’re the natural heirs of John Cooper Clarke.

each dead pheasant you pass

fluttering like a ball gown

in the motorway breeze,

each blurred wasp you see

pulped on the windscreen

('Inland')

and from 'Quake':

for months

I’ve been saving hope

in a blue pot-bellied jug.

But tonight I let it out

and it ran like a cat.

I reckon the key words that give these lines their particular music are "flUttering", "blURRed", "pUlped" … and "blue", and "jug" and "out". Try to hear them with an RP accent and they lose their fullness and weight. The same happens with the words of Clare Shaw (who comes from the west side of the Pennines, where "hair" and "chair" rhyme with "fur"):

Years ago when I was young enough

to eat mud and be interested

in stones and clocks and buried bones –

when I was that young

I found a bird that couldn’t fly.

All the music of this is in those ‘u’s, aand ‘o’s (long and short) … ‘young’ … magine that you hear that ‘g’ ...’mud’, ‘stones’, ‘clocks’, ‘bones’, and in RP it goes flat and tuneless. Just two more. Probably they’re not needed for the argument, but I’m self-indulgent, and enjoying myself. Christy Ducker, first. A different ‘north’, this … the sprung dance of Northumberland whose vowels are brighter than those of the industrial Pennines, and whose inflexions rise rather than fall:

Too often roadkill or sprung space,

our deer survive and come back north

pressing themselves to the house for warmth

('Deer')

and Steve Ely, who relishes the long ‘o’ and short ‘u’ sounds of the north, but also the textures of alliteration, and the heft of consonants:

At bay in wounded country, panting across

the loping snowfield for santuary of pines,

hounds bungling the line through folds of worried sheep …

('Werewolf')

The poets and poetry I respond to are northern

And oh, I’m a sucker for the landscapes of thin soils, hard stone hills, deer and snow. I wrote some time ago that the poet Roy Marshall said he thought of me as a writer rooted in a place. I wrote this in response:

"... if I’m from ‘a place’ I think that place is ‘North’ and my thinking and imagery is ‘North’. The poets and poetry I respond to are northern. I don’t ‘get’ poetry written out of warm or hot or lush or metropolitan or exotic landscapes. It’s my loss but there it is."

And please, if you’re from the ‘south’ and think this is just another bit of chip-on-the-shoulder, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, grim up north and proud of it piece of nonsense, please note that last sentence: "It’s my loss, but there it is." I’m bound to the north, however evasive it is, and, like Ian Duhig, and like Steve Ely, I love the history of its languages and dialects. So, last word to Ian Duhig (and with a silent prayer that the midline breaks will stay where they should be):

Long Will

Langland’s my name long gone from this land

where lettered and lout alike my tongue lashed;

I’d flay fellowclerics for failing their flocks

as fast as the riffraff for riot and wrath,

as fiercely as princes who prey on the poor ―

wealth is mere theft wed into or won,

inherited wealth as heinous a haul.

My poem gave watchwords to Wat’s men and women

who rose in rebellion against England’s wrongs.

Now I’m brought back by a fart of a bard,

to rage and to rant in my rum, ram, ruff staves —

a rough and rude roar in my own raw age,

a savage sound now upon this sod’s soft ears.

I’ll make his ears smart your sorryarse sinner,

a smug poetaster, posturing penpusher

who’d write off religion as simply a relic

of spent superstitions from centuries past.

He’d sneer at the prayers of penitent paupers

whose hope in His heaven is all hope they have;

he’ll tell you that medicine mends all ill men —

what pills or potions preserve poisoned souls?

Paul’s letters that kill are the kind of this clerk,

vanity’s vessel, void of all spirit.

Where I look with longing for lines true and straight,

the pen cutting plain as Piers’ ploughshare

unveeringly drawn from verseend to verseend,

I find instead fiddling as fancy as Frenchmen’s

or rhyme chancer Chaucer chose for his poesy;

where I look for rhythms rum, rough and ramming,

wholesome and heavy as ploughhorse’s hooves,

I’m bored stiff by beatless, babyish rattlings,

unmeasured metre men’s feet can’t march to;

no clashing of consonants but cowardly vowels

softening such combat to simpering songs.

His maundering minstrelsy’s destined for mulch,

pulp spread like gullshit in Piers Ploughman’s wake,

feeding His fields for heavenly bread

whose hymns and hosannas will rise sweet and high

when people will praise without poets’ help

the grandeur and glory of God and His works.

PS: As Tony Harrison also wrote: "Uz can be loving as well as funny."

For further reading

Ian Duhig, The Blind Roadmaker, Picador

Gaia Holmes, Where the Road Runs Out, Comma Press

Christy Ducker, Skipper, Smith/Doorstop

Steve Ely, Werewolf , Calder Valley Poetry

* Phonetic spelling of the word "as"