Pamphlets, collections, and a polished gem: Christy Ducker

Every time I go to an open mic or a poetry reading, like as not I’ll come home with at least one (or more) pamphlets (or chapbooks … more of that later). More likely than to come home with a new collection. Simply because there are a lot more pamphlets about. So I thought I’d indulge myself for a bit and speculate about why.

The simple answer is that if you get to the point when you’ve written a good few poems, and had one or two published, you’re itching to have a ‘proper book’ that you can take to sell at readings, once you’ve done the brazen but necessary thing, which is to ask if you can be a guest reader. You’ll have noticed that last week’s guest Gránne Tobin highlighted the business of feeling awkward about getting your work ‘out there’.

She went by ferry and train to Blackpool, to read her shortlisted poem in the libraries’ Wordpool competition, but they didn’t know she was there. She says: “I didn’t know I should be pushy about declaring myself, so I sat awkwardly in the audience waiting to be called on, and someone else read it. Let that be a lesson to me.”

So, you’ve got pushy, and now you want to be published. I remember that seven years ago when, at the age of 70, I was starting to take this poetry business seriously, I considered the business of submitting work to publishers who just might take a punt on publishing my poems. At that point I decided that the likely timetable could run to a couple of years, and that I hadn’t got that kind of time. So I published my own pamphlets. I thought I could probably edit my own stuff, do my own designs and page settings, and I found a friendly local printer who was enthusiastic about the idea. He showed me how to set up a page template, and we were in business. He was willing to work in smallish quantities. I ordered print runs of 50 at a time, and each pamphlet went to three print runs. They’re all sold now, and paid for themselves. Which is nice. So don’t be afraid of the idea of self-publishing; what have you to lose?

The other thing I did was to enter pamphlet competitions. I didn’t expect to win any but it gave me a context for organising the work. And I was lucky. I won three. The thing is, you can’t win if you don’t play. And there are plenty about: Prole, Paper Swans, Indigo Dreams, and so on. It’s worth thinking about.

If you do decide to have a crack at self-publishing, it’s worth noting that an A5 pamphlet will be 36 pages of text. Which is nine sheets of folded A4 (a lot of small printers don’t do ‘perfect bound’ which means that 18 sheets of A5 are held together by adhesive along the spine … like a Penguin paperback). The thing about folded pamphlets is that they’re centre-stapled, and staples look cheap. The Poetry Business pamphlets offer the model solution. You put a dust jacket on them. And that gives you space for endorsements (on the back) and biographical details (on the turn-ins). If you’re wondering, as I have, what the difference is between a pamphlet and a chapbook, I used to think chapbooks had to be perfect bound. Apparently not. In fact, I can’t find anywhere any two articles that agree on what the difference, if any, is. What is certain is that they will be somewhere between 36 and 40 pages.

If self-publishing seems a bit of a stretch, it’s clear there’s been an explosion in the number of small publishing ventures that are turning out pamphlets by the hundred. In my neck of the woods, for instance, three have opened up in the last couple of years: Calder Valley Poetry, Yaffle, Half Moon Books. The same will be true wherever you are.

Follow this link and you’ll find five closely printed pages, like this. You’ll be spoiled for choice.

The other thing that bothers some would-be pamphleteers is whether they need to be clearly organised round a mood or a theme or a topic. It seems to me that most first pamphlets aren’t.

My first one was a case of choosing what I thought were my ‘best’ poems. As was the case with a reader at our poetry open mic, the Puzzle Poets Live this week. Adrian Salmon introduced his new pamphlet Moonlight through the velux window [Yaffle. 2019] with that very point.

The very first pamphlet I ever bought was Kim Moore’s If we could speak like wolves, which like Julie Mellor’s Breathing through our bones was a winner of the Poetry Business pamphlet competition. Neither of them have an overt central theme. What holds them together is a consistency of voice, and a careful sequencing so that each poem unobrusively follows on from the last without any violent or sudden shift of tone.

I suppose the other thing to make sure of is that you have surefire first and last poems. That’s as definite as I can be. Which is not to say that if you have a single theme that you’re passionate about then you shouldn’t trust it and follow it. My standout example here would be Keith Hutson’s Routines [Poetry Salzburg 2016] … sonnets about the forgotten stars of music hall from the 19th century to the 1950s.

My second pamphlet turned out to be an autobiographical and biographical response to three generations of my family. I didn’t set out to do it. I just found that I’d written poems along the way that fell into that pattern. Happy accident. The only rule that’s helpful is that you should aim to offer readers a sampler that’s unified by your particular ‘voice’. Go for it.

And of course, once you’ve done it, you’ll be thinking about a collection. In which case you really will have to think about the business of submitting to publishers. I can’t help you with that. My two collections are each the result of winning competitions; as are two of my pamphlets. On the other hand, it seems not unusual that a collection will contain a sequence that is so self-contained it could stand on its own two feet as a pamphlet. Fiona Benson’s Bright Travellers is centred in her experience of childbirth, and the trauma of miscarriage, but there’s a cluster of poems exploring the archaeology of the south-west, and a standout sequence given their titles by Van Gogh’s paintings and narrated by his imagined abused lover. Right at the heart of Kim Moore’s The art of falling is a sequence ‘How I abandoned my body into his keeping’ that could happily stand on its own. Which, I guess, is a clunky way of shifting your attention to a poet and collection I think you’ll be happy to meet.

I first heard Christy Ducker reading with Jonathan Davidson at Bank Street Arts in Sheffield a couple of years ago. I wrote this about her in a review for the Compass magazine not long afterwards:

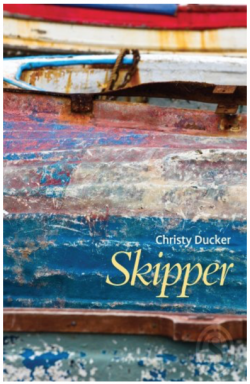

“For the record, at poetry readings it’s the tune I hear, first. The words come after; it’s the rhythm, the space of vowels, the textures of consonants. It’s the authentic accent, the distinctive voice. Sometimes words read at leisure don’t live up to the memory of the voices, but not so with Skipper and its clear-eyed concern for the business of setting the record straight.”

Christy Ducker’s voice has the rising inflexions of Northumbria, the dance of its dialect, its crisp consonants … and so does her poetry. Four clear themes run through Skipper, her first full collection: the way a love affair and a marriage might, wonderfully, be the same thing; the transformations of childbirth and motherhood; the indignities of hospitals, of surgery; the elusiveness of historical truth.

The tone of Skipper is set in the first two poems. ‘And’ proclaims its utter surprised delight at the birth of her son:

and I am astonished

by the way you smell of bloody bread

…

And I know the glee

at the indignant heaving bellows of your belly

The one word “glee”, and the nailed-down rightness of “bloody bread”, that iron and yeast, tell you right away that you’re in safe hands. The second poem ‘Skeletons’ sets the reader up for her explorations of the collusiveness of ‘history’ and its ethical claims. Considering that you might trace your stock back to the owners of, or traders in, slaves, she asks

At what point do we say There. It stops there

and decide to forgive.?

I like the qualified answer, that “perhaps”, when she considers the case of her husband’s family “who used to duck witches”, or of her mother-in-law’s ivory box. Because this is love, and this is family, and because this man rescued her from drowning:

Perhaps it’s the point at which I might learn

to love the present flesh that softens bone.

There’s a salutary entrée to the sequence in ‘Meet the Victorians’ in which the poet admits how she went to the story of Grace Darling with feminist/revisionist intentions,

Expecting a sermon, but finding an orgy

of sorts, I realise I’ve packed the wrong things

The wrong things, that is, to deal with a raucous Queen Victoria, a playful Darwin and all the dubious affairs of the Victorian underworld, for instance. So how does she deal with the “fiercely literate” Grace? The solution turns out to be simple and brilliant. A pamphlet-length sequence of 27 poems chart Grace’s life through her gradual mastery of numeracy and literacy.

In ‘Grace Darling learns to count’ each numeral becomes a mnemonic and an ideogram of her island and its landscape.

2 is a neb-nosed duck out paddling

a plane for wood or a girdling pan,

it’s the cold squat of yesterday’s iron

and

10 is your mother at her spinning wheel.

It’s a beautiful idea which is sustained through the 26 poems of ‘Grace Darling’s ABC.’ : a poem of three precisely weighted regular quatrains for each letter. Christy Ducker plays with the graphics of the letters..

A

is the point of intention

she sees at the tip of her pen

which is also a tool to carve out her alphabet. O, memorably, is the coins she earns from salvage, “flat as the faces of drowned me / she pulls from the sea like moons.”

E

is the flight of three small steps

she climbs to reach the lantern room’

and also the letter "that warms all vowels." In these regular, eight-syllabled lines she explores the letters’ shapes, their assonance and consonance and weaves them into a story of Grace’s growing into womanhood and difficult celebrity.

Christy Ducker also reminds me of the way museums seem to sentimentalise embroidered samplers; she, on the other hand, makes you remember poor light, sore fingers, the physical work that underlies achieved literacy. Every poem is full of unobtrusive slant rhymes and assonance, of surprising true images. My favourites?

J

is a hook that hangs by a thread

in the vault of the North Sea

where it inkles, bright as her faith

the fish will come.

and

U

is the round-bottomed coble

she punts across the page to write

‘our Universe, or keep ‘us’ afloat

but you can take your pick. If I was allowed just one word to describe Christy Ducker’s writing in this collection it would be canny; a Northumbrian word, weathered and layered and rich as the patched hull of the boat on the book’s cover.

So, there you are: I’m a fan. Christy is a poet and teacher of creative writing. Before Skipper was published in 2015,. Her pamphlet Armour (2011) was a a Poetry Business Pamphlet competition winner. Her commissions include residencies with Port of Tyne, English Heritage, and York University’s Centre for Immunology and Infection; she is also the director of North East Heroes, an Arts Council England project. You can see what she’s up to via this link.

Since Skipper was published, she produced new poetry pamphlets in collaboration with artists. Heroes was illustrated by Emma Holliday’s gutsy linocuts, and Messenger was in collaboration with Kate Sweeney, whose photographs accompany the poems throughout.

What can I say? Go and buy the books. And come back next week when I’ll be reviewing two new pamphlets.

Skipper, Armour, Heroes and Messenger are all published by smith|doorstop, and available from the Poetry Business