Instagram poets pushing us off bookshop shelves, warns Bloodaxe's Neil Astley

The highly successful Bloodaxe Books publisher Neil Astley has highlighted the changing nature of poetry book sales as a result of the internet, and the rise of Instagram poetry. In a Q&A session at Barter Books, the famous secondhand bookshop in Alnwick, Northumberland, at the launch of a new collection by Bloodaxe poet Katrina Porteous, he admitted that online purchases were affecting book sales, with Bloodaxe’s biggest customer now Amazon, when previously it had been Waterstones.

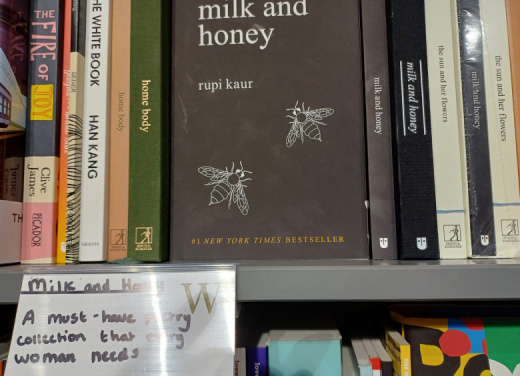

He also pointed to the sales success of some Instagram poets, describing their poetry as “short and pithy” but amounting to “bits of sentences chopped into lines”. He added: “Our books are being pushed out from bookshop shelves by this amateur stuff."

Instagram poets are those who post their poems on Instagram initially. Some accumulate many thousands of followers, enough for mainstream publishers to offer to publish them. Scottish poet Donna Ashworth ended 2023 with five of her books in the Top 20 poetry chart, and three of them in the top five, after posting her poems on social media. Write Out Loud also uses Instagram to showcase the talents of poets that blog on our site from time to time.

Astley told the audience in The Old Waiting Room at Barter Books, which is housed in a former railway terminus: “The pandemic changed the way books are bought … but we’re still enormously helped by independent bookshops. You’ll discover things in independent bookshops that you won’t find in Waterstones, because Waterstones are now all the same.”

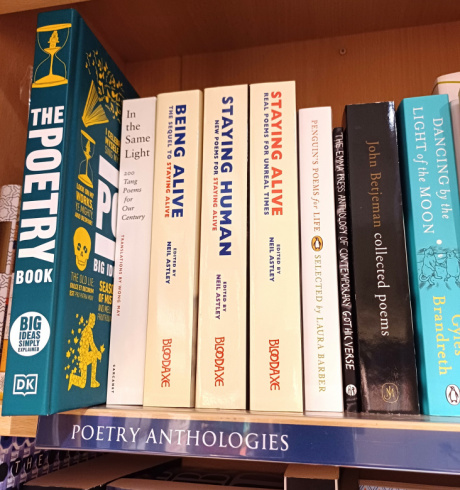

Neil Astley and Bloodaxe are particularly well known for their bestselling anthologies over the years, such as Staying Alive, Being Alive, Being Human, and Staying Human. Others have included Soul Food and Soul Feast, the latter published earlier this year.

Almost 20 years ago he talked of Staying Alive, the first anthology in the hugely successful series, as introducing “thousands of new readers to contemporary poetry. It also brought many readers back to poetry, people who hadn't read poetry for years because it hadn't held their interest. Too often, poetry editors think of themselves and their poet friends as the only arbiters of taste, only publishing writers they think people ought to read and depriving readers of other kinds of poetry which many people would find more rewarding.”

Bloodaxe will reach its 50th anniversary in 2028. Astley told his Barter Books audience that he launched Bloodaxe because “no one else was publishing the kind of poets that interested me. The idea was to give readers a broad range of poetry that excited me.”

As Katrina Porteous talked about the ease with which poets were able to self-publish these days, and a lack of “gatekeepers”, Astley also had some points to make about the process of editing. Porteous said he was “quite unusual”, in that “you hardly intervene in the writer’s work at all”. Astley replied that that wasn’t always the case, but added that there were some poetry editors, also poets themselves, who were “quite notorious …sometimes they want the poet to sound like their own work”.

He added that when it came to putting together a collection, he was sometimes sent a group of poems that had all been published in magazines, “and they think that’s a collection, but it often isn’t. As an editor it’s your job to find the poems that work as a collection.”

As far as poetry book sales are concerned, there was one bright note at the start of the evening. Mary Manley of Barter Books - once described by the New Statesman as “the British Library of secondhand bookshops” - said that contemporary poetry was one of their biggest-selling genres of used books. That has to be good news. Hasn’t it?

Bloodaxe anthologies on sale at Blackwell's bookshop in Newcastle

Books by bestselling Instagram poet Rupi Kaur on sale at Waterstones in Newcastle

Steve White

Sat 13th Jul 2024 08:05

If you're in the business of selling poetry books and fewer people are buying your books, preferring to read poetry on the internet instead, then criticising their choices is hardly likely to have them come flocking back, and Astley comes over as particularly pompous with his "bits of sentences chopped into lines" and his later accusation that editors only publish work that they think people ought to read but then going on to say that he launched Bloodaxe to publish poets that interested him.

There are advantages to publishing your poetry on the internet. If you're writing about contemporary events, you can share your reaction while those events are still current and in the forefront of people's minds. Stephen Gospage's commentary on the war in Ukraine, here on Write Out Loud, springs to mind. There's also no doubt that the Instagram poets are reaching and engaging with audiences whose last interaction with poetry anthologies was probably at school.

There are downsides, of course. By publishing your work on the internet you are giving away something for which you ought to have been paid and there's is a heightened expectation from consumers of music particularly that it ought to be free or at least available on an inexpensive subscription model.

Like it or not, Astley's business operates in a market economy. Telling your market that it's wrong or exhibiting poor taste is not how it works.