Remembering a ground-breaking book of poetry, 50 years on

“They called the book The Mersey Sound. We didn’t want it. It looked as if we were cashing in on the Beatles – and of course we were. We were christened the Pop Poets – not as in Pop Art but as in pop music – and the implication was that we’d be here today, gone tomorrow.”

That was Roger McGough in 2013, talking about The Mersey Sound, which was number 10 in a series of slim paperbacks originally published in the 1960s by Penguin in a series called Penguin Modern Poets. It featured Liverpool poets Adrian Henri, McGough, and Brian Patten, and unlike the others in the series it became a poetry bestseller.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of its publication, and in the first event of 2017 to mark the occasion McGough and Patten - Henri died in 2000 - will be appearing at Liverpool Playhouse on Saturday 28 January along with the poetry to music band Little Machine.

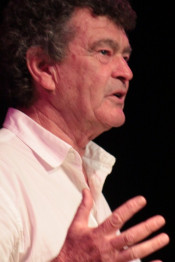

The Mersey Sound is credited with making poetry more accessible to people, with Henri, McGough and Patten seen as the forerunners of performers such as John Cooper Clarke, Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Benjamin Zephaniah. Talking about it some more at the Troubadour in 2014, McGough, pictured below, right, who also went on to top the charts in the 1960s with the novelty pop group Scaffold, explained how he failed his Eng Lit O-level at 15, and couldn’t get his head round the kind of poems he found in Palgrave’s Golden Treasury. When he went back to school, to teach, he was once more handed the Golden Treasury. His class didn’t seem to like it any more than he had, so he gave them some of his own poems, that he had been reading at Streats coffee bar on Monday nights with Brian Patten, Adrian Henri, and others, “poems about my aunties, or football, and they liked those, and so I thought, maybe I’m writing poetry”.

“At the early Liverpool readings c1961 our audience would drift up from the Cavern where the Beatles had started playing to the poetry gigs we organised in a club called Streats. They were office workers and secretaries and manual workers as well as students, or like myself, kids that had left school at 15. Any pretentions the poetry had about being exclusive would have been given short shift - one wanted to be honest to one’s own muse and to the audience as well. We shared the same points of reference, and had a language in common. Also we came from working-class backgrounds - Roger’s father worked on the docks and mine was a merchant seaman.”

In an article for Write Out Loud, former Merseysider and journalist Maggie Lett recalled those heady times in 60s Liverpool, and being introduced to poetry “that was both irreverent and accessible and in my own language, poetry about the fanciful, about the heart without all the red-rose guff, or which uprooted the daily mundane into the realms of wonderful wordplay. Poetry suddenly could be fun. It was all very Liverpool, that combination of humour and directness, here deceptively simple thanks to the skills of the writers.” She became good friends with Adrian Henri. “If I was at the poetry night on my own, he would walk me to the bus station afterwards and I’d often visit his flat in Canning Street when I was in town during the day. We’d talk about all sorts of things - life, religion, the visual arts and the art of words (sounds very pretentious now). I can remember feeling that lowly me from Bootle had joined the avant-garde set the first time I went to Adrian’s place. Immediately through the door, hanging on the landing wall, was a tyre-less bicycle wheel with a bloody dead bird squashed through its spokes."

A closer friend of Henri’s was today’s poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy, who met him when she was 16, and he was 39. In an interview with the Telegraph in 2010 she said: “I was terribly in love with him for many years. And we were always very close – I was with him when he died.” She and Henri were together for about 12 years. As she has said elsewhere: ‘It was all poetry and sex, very heady and he was never faithful. He thought poets had a duty to be unfaithful.’

Shahzadi Punjabi

Sat 26th May 2018 11:58

Thank you Gough, Patten, Henri for making poetry so accessible to the likes of me.