My kind of poetry: Gaia Holmes

Gaia Holmes's third collection was recently longlisted for the RSL Ondaatje prize. That’s all the prompt I need to revisit things I’ve written about her in the past, and to urge you to rush out and buy it forthwith.

It’s hard to keep track of what’s about, what’s in, what’s out in the bubble of the self-defining poetry world. New collections and pamphlets and chapbooks appear on a weekly basis, and of the ones I manage to get hold of some are good and some are not, and some are so-so. Only a very few are special, ones that haul you in, won’t let go, make your nerves and your heart more alive and alert. This one from last year is the third (and, I think) the best collection yet from Gaia Holmes: Where the road runs out.

I’m frequently surprised by the number of poets I know that don’t know about her. I was at the Poetry Business recently and enthusing about her to as many folks as would listen. About half of them didn’t know her work. She seems to be one of those genuine stars who fly below the radar. It’s my mission to correct this state of affairs. Let me introduce her:

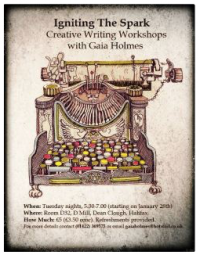

There are many poets around Calderdale that will testify to the richness of these workshops, my publisher Bob Horne, and the hugely talented Natalie Rees among them. Her first full-length collection, was Dr James Graham’s Celestial Bed in 2006. and her second Lifting the piano with one hand in 2013 [both published by e Comma Press]. The American poet Joan Jobe Smith has called her "my favourite contemporary female poet". She’s not alone in that.

Jane Draycott talks about the point where a poem detonates. Gaia’s poems often put me in mind of chemistry lessons in the blissfully pre-health and safety 1950s, when to demonstrate the meaning of the word crepitation a teacher would toss a slack handful of crystals (potassium?) into a sinkful of water and stand well back. So many poems in Where the road runs out detonate in line after line, like dangerous Rice Krispies. But because many of her poems are about separation and loss of love or lovers, and in this collection, of a father - sometimes tender and sometimes vengeful, sometimes wistful and sometimes heartbreaking - they also take a reader into dark woods and lose her. Like this one:

Road Salt

Snow falls plumply, prettily,

whites out the dog-eared leavings

of Christmas,

dolls-up the ragged end of January,

mutes the road between us

with its whispering glamour

and we’re stuck –

you in the East and me in the West

with miles too thick and deep to cross

and, once again,

without you, I fall asleep

listening to the frost

patterning the insides of my windows,

laquering the edges of my bed.

If I could

I would send you

seal-skin boots and brandy.

I would send a sledge

and a savvy husky to guide you

across the blinded miles,

but instead I go out

into the bright, dumb darkness

with my pockets full of road salt,

toss it to the night

like chicken feed,

try to melt myself

a path to you.

The Allure Of Frost

Boxing day.

No fire in the grate and unopened presents

stacked around the base of the tree and fairy lights muted,

switched off, and the brandy that swells the fruit starting to eat

the cake in its tin and all the mirrors doused with tea towels

and your raw-eyed mother keening into a pillow in her bedroom

and too many men in black whispering and nodding

and I don’t know what the rosary is and whether to curtsey

to the priests when I hand them their tea

and the phrase ‘fruits of thy womb’ seem too ripe and too rich

for this and, Mary mother of God, I don’t know

how to cross myself and fear I’m invoking the devil

and the scent of death’s so thick

that it’s tainted the water and it’s heavy in the curtains

making them bend the rail

and your lips taste of the oils that grease your dead sister

and when I kiss you, you push me away and I want to spit

and weep and slap the corpse where she lies in her coffin

all done-up with hair grips and lipstick,

her sunken cheeks plumped out with wads of cotton wool

and the rictus of sin softened

by the crust of Rimmel Natural Beige powdering her face

and it’s so hot in here

that the cheese is sweating and the butter is liquid.

The chocolate coins are dripping from the tree.

Your Aunt’s un-bitten sandwiches

are curling upwards on her plate

and the lilies are wilting and stinking in their vases

and the cat stands quivering and retching

against the cold crack beneath the back door.

Outside the frost, not knowing any difference,

continues to sparkle. And I’d like to go out there.

I’d like to stand in it until my feet turn blue.

I think this has everything in it that I think of as a Gaia Holmes poem. The piling on and on of sensory detail, the Alice in Wonderland sense that the logic of things is wrong; the wistfulness, the vulnerablity, and the pluck of a girl who will stand in a sparkling frost till her feet turn blue and the world becomes real again. It also has the undertow of a diffuse guilt about religious uncertainty:

and I don’t know what the rosary is

… and, Mary mother of God, I don’t know

how to cross myself

There’s a more worldly voice, too. I’m struggling to make up my mind about which poem to choose, but I plump for this one:

Ballast

You reach a certain stage in your life

when you seem to spend a lot of time

holding other people’s babies.

At parties, the bottles of M & S berry crushes

on the kitchen table

outnumber the bottles of wine

dand it seems you’re the only one drinking.

Tonight you’re nursing your second glass of Chianti,

warming it against your chest

as the other guests sip Mocktails

and talk of teething rings and Farley’s rusks

and you’re trying to find a way in, but failing

and one of the kids is doing that cute thing again

with his hat pulled down to his nose

and everyone starts taking photos

and clucking and cooing and you take one too

just to fit in, even though you know

that you’ll delete it later

in favour of a landscape

or something you can understand

or something you can have

and you want a cigarette but no one’s smoking

so you go and stand outside the front door in the sleet

to smoke a roll-up but it gets wet

and you’re sucking on nothing

so you go back in. You cut through the branny fug

of milk and nappies with your reek of smoke

and they look at you cow-eyed with pity

and you know they’ve been talking about you

and one of them says “It’s not too late at forty”

and you mumble something and walk into the kitchen

to pour yourself another bigger glass of wine

and you sit there for a while listening to them talking

and think about the things they have:

the husbands, the high chairs, the family-sized toasters,

the pairs of tiny red wellies lined up by the door,

the huge American fridges

covered with glitter-crusted playschool pictures

and you think about your lack.

You think about your cat that moved next door,

your scrawny Basil plants withering on the windowsill,

the bread you bake always turning black

and you go back into the lounge,

move mounds of small, pale woollen things off a chair

and sit down wishing you had some ballast in your pockets,

wishing you were not made of straw and dry things,

wishing you were not quite so old and flammable

because they’re all looking at you

and it seems you’ve turned into

the hollow witch levitating in the corner,

that lonely, awful thing

that they could have become.

In case you should think that the world of the poems is always cold and frost-bound and the heroine ‘helpless’ there are poems like 'Rain charm for Stirling Street' that are funny, extravagant, and where the heroine becomes downright gleefully dangerous:

Rain Charm for Stirling Street

Oh, the itch and nag of it -

… in the fridge

milk thickens and clots

in the necks of bottles,

the cheese gets louder and louder

until it roars.

…

I am taking action.

I am standing behind the kitchen door

wobbling a cross hatch saw

to make the sound of thunder.

I am cooking lightning

in the microwave.

I am pouring rice on to a saucer

to make the sound of rain.

I am summoning a storm.

You know what? I believe Gaia Holmes can make rain. I know that cheeses can roar. I take that as the West Riding dialect word for ‘weeping’. ‘Give ovver roaring or I’ll give you summat to roar ovver’ my gran would say.

There are so many riches in the collection: the joy and lyricism of 'Hope',, the wild fantasy of 'Imported Goods', the quiet and accurate observation of 'Bloom', the indignant comic voice of 'The Runners Versus the Ramblers', the psychic dark of 'Shadow Play', the surrealism of 'Last Orders at the Light Bar' and 'There was Just this Monstrous Hole …' And then there’s a sequence, 'Remembering Light', about the trapped Chilean miners of the San Jose mine in 2010. If that was all there was, this would still be a stand-out collection.

What takes it to an altogether different level, however, is the sequence that opens the book, and which is referenced at several points throughout. Some collections have at their heart something particular, powerfully felt, personal and universally engaging. Where the road runs out is made remarkable by the poems which deal with the death of Gaia’s father.

David Holmes, you learn through these poems, was a stubborn, fiercely independent, difficult and, in more ways than one, remote father. A potter, he lived on a small bleak Orkney island, treeless, stormswept. Elwick Mill was a recalcitrant renovation project, and David mainly lived in a caravan on the property. Over many months, Gaia, her brothers, her mother, her partner would make the long journey north, where the roads run out, to nurse him (which he fiercely resisted) in the late stages of his terminal cancer. Finally, Gaia was with him in his last days, and these are last days' poems. The book begins by putting you in the landscape:

And Still we Keep on Singing

Up here the hours go backwards

and we’re closer to the edge of things.

Up here you have to know the language of the wind,

you have to understand the manners of mist and riptides

in order to go to sleep singing,

in order to wake up

on the brighter side of life.

Some days sunlight sugars the island.

Cats lie on their backs bleaching their bellies,

seals bask on the rocks, braise their lovely fat

until it’s close to boiling point.

Orange crocosmia burns gently

around the mill dam.

Every kitchen smells of bread .

The world hums as it hangs out its washing.

Other days we gag on the reek of drift tide rot.

Broken gulls and fulmars

float in the harbour

like oily rags.

Damp socks and dresses

freeze and stiffen on the washing line.

A furze of haar blots out our thin and precious light.

The glow of the mainland, that cosy grail we cling to,

that glimmer of cars, buses, shops and living,

disappears in to the dark, monstrous mouth

of the island where lightbulbs shatter and fuses blow

and we’re left with singed fingers, the thick stink of wax

and candles whose wicks are too damp and weak

to sustain a flame.

The image of the candles is real and perfect; things cling to life and light and warmth, but the whole business is ultimately exhausting.

My father is fevered and godless.

My father is dying on an island

with no trees.

I send him prayers.

I send him bulging sacks of autumn leaves.

('Leaves')

In his caravan with its cracked windows, hugging "the damp, your denial". this father surrounds himself with "the lying dog-eared books / How to outsmart you cancer" and his daughter has to assert that

I belong here,

Mistress of Haar, Our Lady of the Seals,

your angel, your fumbling nurse, your little star,

stumbling around in your size 10 wellies

and your clay-crusted fleece,

stubbing my toes on shadows,

('I Belong here')

Those who have never had to care for the terminally ill or the terminally old might not anticipate that their care and their love can be received by what seems like ingratitude; the dying can be awkward, cantankerous, bloody-minded, resentful. They can be in denial, and they are strangers to serenity. Maybe it’s fear, or maybe it’s some visceral survival instinct. But to the carer, believe me, it hurts. I thought I’d understood and dealt with my mother’s protracted dying, but these poems shone a new and healing light on it. They do what good art should do, they enlighten, which is a layered word if ever there was one. These poems will strike a chord with, potentially, thousands of children and partners who thought no one understood that “grief needs feeding" ( 'Kummerspeck') because you have no choice, and would want no choice..or you’ve chosen, because, as the poet says, defiantly, "I belong here / with your dying / and every dawn sky / seething / and blistered / with stars." It’s defiance that’s needed in the teeth of anger or frustration,that no one can condemn in the dying:

Sometimes it makes him angry, this dying,

and I keep doing things wrong,

…

Forgodsake, he says, still strong enough

to make the caravan shake,

to make the clock fall off the wall,

to scare the fat white cats

from where they lay

scorching their fur on the gas fire.

Forgodsake.

And I know that I’ve lost

my angel’s status

but I’m trying

…

Forgodsake.

The island whimpers

and trembles beneath us.

There will be bruises

in the morning

…

Forgodsake, he says.

I sit at his bedside sucking my knuckles

until he slips in to fevered sleep

then I jog barefoot around the mill

in the frost to remind myself

that sometimes I need to suffer.

('Feckless')

There it is again, that image of self-mortification, and the salt shock of frost that tells you you are who you are, and you are real. There are moments of respite, though and they come quiet and healing, especially in these extracts from 'Hygge':

Tonight, with you calm, clean,

smelling of lavender in your new pyjamas

...

I light all the candles I can find,

put Tallis on the stereo, sit holding your hand.

Tonight, the sea will be too wanton

to carry a ferry.

…

Tonight we will keep the cats in.

Tonight, we will be landlocked and cosy

…

Tonight I will feel your knots unravelling,

our bond thickening

as love and thin motets chase the cold

from the corners of the room,

and I will almost forget that you are dying.

Stone Soup *

Up here every night,

just for the hope

and the blessing

of something steaming

and bubbling on the hob,

I cook us stone soup.

The thin broth

tastes of the sea,

reminds you of how,

only weeks ago,

you’d scramble

over the shingle,

happy to bruise your shins

in the Bay of Balfour,

gulping down the briny air,

savouring its myth,

its tang, its babble.

Now you are bed-bound,

landlocked

so I tack a crumpled sea-view

from an old National Geographic

across your window,

bring the tide home

in old pickle jars,

pour grains of sand

into your cupped palms,

sing you to sleep

with hissing lullabies,

press crystals of salt

onto the tip of your tongue.

What will survive of us is love. I keep typing that. What I want now is for this collection to be given the recognition it deserves, I want it to win prizes, and I finally want to be able to tell poets about Gaia Holmes, and not need to explain who she is.

Gaia Holmes’ poetry to buy:

Dr James Graham’s Celestial Bed, Comma Press

Lifting the piano with one hand, Comma Press

Tales from the Tachograph, co-authored with Winston Plowes, Calder Valley Poetry

Where the Road Runs Out, Comma Press

* For anyone puzzled by "stone soup", it’s made from cunning, resourcefulness, self-belief and hope. First, catch your stone.

<Deleted User> (5011)

Fri 17th May 2019 17:31

John, thank you for this marvellous - nay, magnificent - reminder of Gaia's quiet brilliance.

I want to support your thesis, that Gaia is an underreported gem of a poet. On this evidence, her flower should no longer "remain to blush unseen", as Gray put it.

For me, the judge of what makes a superb poem or line, as opposed to a good one, is the physical effect on me, the hair on the nape of the neck test, that frisson of which there is an abundance here.

And when that thesis is as well penned as this, it has similar effects. Wonderful writing about wonderful writing. Thank you.