Writing poems in the sleep of reason

I remember one of my uncles, a lifelong trades unionist and old-style Labour man. He was an interesting man; he completed his Open University degree when he was 80. He once told me that the cleverest thing the Tories ever did was to introduce the Giro. His argument was that when you were unemployed and drawing benefit, it came through the letterbox in an envelope. He said that when he was a young man in a time of mass unemployment and poverty in the 1920s and 30s, men went to the Labour Exchange to draw the dole. There’d be queues along the pavement; what else was there to do? So there was an audience for the political activists of all persuasions. He said that was how people became politicised (unless they clung tenaciously to their membership of the Ragged Trousered Philanthropists Union).

I remembered that story when I was teaching A-Level communication studies, getting students to critique the concept of mass media. I forget where I read it, but I came across an interesting argument to the effect that Goebbels understood the principle of mass media. One of his plans was to install loudspeakers on street corners where people would have to gather to listen to radio news. I thought of this when we considered the way the Indian government at one point financed the provision of a television in every village. The overt aim was to expand education and literacy. It’s easy to see how both systems were double-edged, but the point of my uncle’s argument held. No one would receive information in isolation, and so information would be shared and communal - and open to debate.

I’m not dewy-eyed about the vision, but as someone who spends far too long on Facebook, I have no illusions that I’m using ‘social’ media, or ‘mass’ media. Media platforms now are essentially individuating, nucleating and isolating. If you read the posts on my Facebook page you’d imagine the world was made entirely of left-leaning, pro-feminist poets, runners, birdwatchers and landscape artists. Whereas when I go down to Sainsbury’s for my shopping and make myself read the front pages of the tabloids (and, indeed, the so-called quality papers) all I see is parallel universes where people speak a different language and live in a completely different country from the one I think is mine. We need no longer meet anyone who disagrees with us. I don’t have to make myself check out the Mail and the Express and the rest on a daily basis. But I do.

We can all ‘publish’ with little effort, and accumulate lots of ‘shares’ and ‘likes’ and smiley emoticons, and almost imagine we’re changing people’s minds. But on my bleak days, and there are many of those of late, I see that I’m at the bottom of a deep dry well, and I can shout all I like, but the only feedback I’ll get is the distorted echo of what I’ve just said.

Lately I have spent days with many people I’m very fond of, reading and writing poems, and I found it all very difficult. Why were we there? What did we think we were accomplishing? Let me rush to say that I have no intention of giving up, but sometimes I need to get it in proportion. And there’s no irony in the fact that when I set out to do that, I’ll turn to poets as readily as to anyone else. More readily in fact.

I’ll turn, say, to Bob Dylan, and go along with the idea that he articulated the anger and aspirations of a generation at point in history, when he could sing for civil rights marchers, and in Washington for Martin Luther King. Songs like The times They Are A-Changin', The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll, and Ballad of Hollis Brown.

I think I thought, at the time, that the songs were changing the world. Not that they were articulating a change that other people were making by direct action and incredible acts of physical and moral courage. I remind myself that he’d probably have vanished without trace at the time of McCarthy, because not enough people would have been ready to listen, and in any case, no one would have broadcast him. There were wonderful things written in the Soviet Union under Stalin and later, but they circulated in secret as samizdat. Thing is, I don’t ever want to forget that Dylan also wrote "When everything I’m a-sayin’ / You can say it just as good" in One Too Many Mornings.

Some days that’s how I feel … everything I’m saying, you can say it just as good. Or much better. And who’s listening, and why should they care? I’m over that for now, but I recognise the irony of writing about the pointlessness of writing. The point is, I think, that Dylan wrote it, and hey, I can’t write it just as good. Which is why I’m borrowing his words.

There’s a demagogue in the White House and millions have marched to protest it. The news media can manipulate that, and they do. They can edit out events, because whoever controls the present controls the past and the future. They can, with apparent impunity, present lies and call them alternative facts. The chattering and privileged classes can have elegant arguments about the concept of ‘post truth’ without ever saying simply that it’s an obscenity. If we don’t hang on to the true purpose of language which is the business of true naming, then we are lost. Auden didn’t bring down Hitler, but he articulated the essential nature of tyranny that lets us truly name a monstrosity like Donald Trump.

Epitaph on a tyrant

by WH Auden

Perfection, of a kind, was what he was after,

And the poetry he invented was easy to understand;

He knew human folly like the back of his hand,

And was greatly interested in armies and fleets;

When he laughed, respectable senators burst with laughter,

And when he cried the little children died in the streets.

And the poetry he invented was easy to understand. There’s a line to cling to. Life is wonderfully and terribly complicated and muddled and difficult. Tyrants understand that language needs to be used to simplify, and to reassure the ones they seek to control that they can make the world comforting and comprehensible. Brexit means Brexit. Give us back our country. You know why Corbyn is unpopular … because he keeps saying it’s not simple, it’s not easy, it’s muddled. He must be muddled, mustn’t he? Weak. As opposed to ‘not a tyrant’.

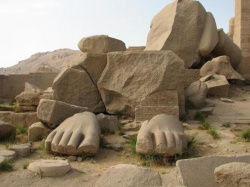

I suspect that poetry is sometimes used in a potent way to suggest that everything will be OK in the long run. There must be thousands of people who know little about poetry, but who have somehow come across this bit of Shelley.

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said — “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert .... Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

I remember at the age of 15 or so the excitement of realising how irony worked. "Look on my works ye mighty, and despair". Hitler and Stalin were both dead by then. Which, I thought, proved the point. Tyranny won’t survive. I guess I didn’t read the rest with any real attention. "Nothing beside remains". That fallen statue lies in a wasteland of the king’s making. There are no people. Nothing grows. I didn’t see that maybe I should look on that and despair; that the past was irredeemable. We read and we hear what we want to hear.

Oddly this makes me want to kick out of the despair, and to write. Because if I know anything, it’s that if I really write … if I really pursue the business of true naming … I may just find that I know things that I didn’t know I knew, or that I would never acknowledge, and I might know the world better. If that speaks to someone else, then that’s a bonus. But perhaps I’m coming to believe that my first reponsibility is myself, and my health depends on speaking truly.

I know this is an incoherent post for a Sunday. Still, I’m inclined to believe that when Matthew Arnold wrote 'Dover Beach' his first purpose was to understand his own spiritual despair …and I’m inclined to think it was in the process of writing that he discovered that there was an answer to that despair.

Dover Beach

The Sea of Faith

Was once, too, at the full, and round earth’s shore

Lay like the folds of a bright girdle furled.

But now I only hear

Its melancholy, long withdrawing roar,

Retreating to the breath

Of the night-wind, down the vast edges drear

And naked shingles of the world.

Ah, love, let us be true

To one another! for the world, which seems

To lie before us like a land of dreams,

So various, so beautiful, so new,

Hath really neither joy, nor love, nor light,

Nor certitude, nor peace, nor help for pain;

And we are here as on a darkling plain

Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,

Where ignorant armies clash by night.

One hundred and forty years ago, ignorant armies clashed by night, and the world was a darkling plain. Sounds familiar? So why am I reading it again, and finding a reason to keep writing. Hasn’t it all been said before, and better? Wasn’t Dylan right? Yes and no … there’s a line I can cling to, like a life raft in a cold sea. It’s not remarkable, except that it’s said in a spirit of apparent hopelessness.

Ah, love, let us be true to one another!

Because if we can’t do that, then we are truly lost. And how can we be true, if we can’t say how. Which is why I’ll go on writing, whether anyone reads it or not.

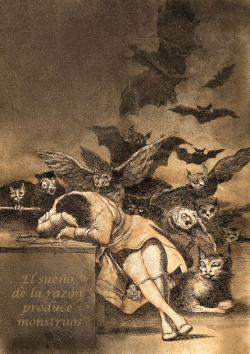

The first illustration is from Goya’s print sequence the Caprichos No. 43 'The sleep of reason produces monsters'. As he explained in his advertisement for the series, he chose subjects “from the multitude of follies and blunders common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudices and lies authorised by custom, ignorance or interest.” In his presidency to date, Trump’s golfing trips cost the public purse $105,000,000. Today Theresa May released a video in which she pays tribute to the Windrush generation. And so on …

[This is an edited version of a post that originally appeared in the great fogginzo’s cobweb. I think it seems just as relevant today as it did then.]

M.C. Newberry

Thu 27th Jun 2019 14:51

Don't all politicians tell people "what they want to hear"? Whatever

his perceived faults, Trump has an unusual non-political origin

compared with the usual "Buggins' turn" sequence that electorates

usually see. Any comparison of Trump and Johnson with the

dictatorships of the past is grotesque in its assumptions of the

intent of either. As for "feeding English prejudice against foreigners"

- again too facile to use as a viewpoint when the Brexit premise is

to regain some semblance of the self-government stealthily handed

without a mandate to control by committee based in a foreign city -

in pursuit of some sort of mythical "Brave New World" in action. Since the word

"English" has been employed in this context - rather than the ubiquitous "British" - it is my experience that they are very much

"a take as you find" breed, historically suspicious of strangers but

more welcoming than most once the ice is broken; justifiably

concerned - like all other countries I suspect - when faced with

insupportable numbers that can cause a worrying imbalance in

social well-being and a hard forged national sense of identity.

Socialists tend to believe in some sort of world order - with no

boundaries In place. Orwell's 1984 has come and gone but

its warnings still have relevance when it comes to a question of

control and how it is achieved.