Confessions of a tripe addict

Lately I’ve been bingeing on Netflix and catch-up and box sets. The Killing, The Bridge, Borgen, Spiral, True Detective, The Wire, House of Cards (the American one); I’ve been reading comfort blanket novels. John le Carre’s The Little Drummer Girl. That sort of thing. In the car it’s Terry Pratchett audio books. You get the picture.

But it’s got me thinking. Where did all that come from? And I think I have an answer of sorts. Tripe. Not the stuff they sold in grim little shops when I was a kid, their small windows displaying horrible, slithery heaps of pale honeycomb, and darker stuff. No. The stuff my teachers dismissed as tripe/rubbish. The stuff I read voraciously. When I was a lecturer in teacher training I used to argue passionately that all developing readers need a healthy mixed diet of books that challenge linguistically, morally, emotionally … but that they won’t handle any of it if they don’t read lots and lots of stuff that’s formulaic, predictable; stuff where they feel comfortably at home. Because they can’t understand when someone is breaking the rules and pushing the limits of what’s possible if they don’t know what those rules and limits are.

I’ll try to illustrate what I mean via a potted history of my own reading, but first, let me share something I read in the 1970s. It’s from a talk, A Defence of Rubbish by Peter Dickinson, author of The Changes trilogy, and around 50 other books.

“The danger of living in a golden age of children’s literature is that not enough rubbish is being produced.”

“Nobody who has not spent a whole sunny afternoon under his bed rereading a pile of comics left over from the previous holidays has any real idea of the meaning of intellectual freedom.”

“Nobody who has not written comic strips can really understand the phrase, economy of words. It’s like trying to write Paradise Lost in haiku.”

I remember how that hit me right between the eyes. It was a revelation. I did an English degree which almost killed my ability to read. I became very good at writing essays that seemed to satisfy some unspoken need in my tutors, but I forgot how to read, and I didn’t learn to read again until I had children who I read stories to. Hundreds of picture/story books; Catherine Storr’s Clever Polly; Flat Stanley, the Narnia books … stuff like that. I remember our Michael and Julie (five and seven) literally danced around the room the night that Charlie Bucket found the Golden Ticket. Because they knew what I’d forgotten. We read stories because we want to know what happens next, and we want to know what happens next because we care about the characters it happens to. And then we want to read it again to reassure ourselves that it’s still real. We learn to value the repeated and the predictable, because real life is neither.

The important thing, I used to argue with my students, is that you need to read a lot of it. You read until you get sick of it and want a change, you want to move on; you want stories to accompany you as you grow and change. So I moved on from the Dandy and the Beano, and the Hotspur and the Wizard. You can guess where to, because you probably did, too.

And so we grow older, if not up. I never quite left William behind (mainly because Richmal Crompton was a brilliant writer) but the Famous Five palled, became irrelevant, the stuff of childhood. I moved on (if not up) to WW2 escape stories, The Saint, the Pan Books of Horror Stories (there were so many of them). I reread most of them many times. Tripe. I supposed they paved the way for James Bond. You get the picture.

The thing is, all this went on in parallel to, and totally separate from, whatever we were expected to read at school. Dull stuff in duller covers. Lorna Doone. The Black Tulip. And ‘poetry’. Paths to Parnassus, Palgrave’s Golden Treasury. Most I can’t remember, because I never read it with interest, and never re-read any of it. Whereas I can remember huge swathes of tripe, in the way I can remember the words of scores of Methodist hymns, and of pop songs. Repetition of formulaic art with variations and surprises.

Maybe if Louis hadn’t set me to copying reproductions of Degas it wouldn’t have worked. But to my complete surprise I was hooked on the first sentence, and I still am. I hadn’t read the book for over 10 years, but when I put it on my Kindle last week, I felt as though I could quote whole chunks of it verbatim.

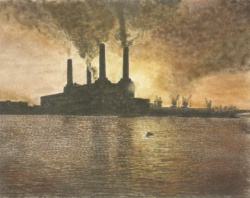

I was walking by the Thames. Half-past morning on an autumn day. Sun in a mist. Like an orange in a fried fish shop. All bright below. Low tide, dusty water and a crooked bar of straw, chicken boxes, dirt and oil from mud to mud. Like a viper swimmimg in skim milk. The old serpent, symbol of nature and love.

I can look at it now as I type, and see that it’s a thing that’s been done and done again. But I’d never have fallen into the rhythms of Ulysses, and I’d never have seen what Gerard Manley Hopkins was up to without that book, and its impressionist prose. The fact that the narrator is just out of prison, and will actually go back there before the book’s halfway through, grabbed me too. And because I was 16, although the book is often described as a comic masterpiece, to me it was pure tragedy. Gulley Jimson chases his vision of the ultimate work of art throughout the novel and it collapses just as he thinks he’s pinned it down. He quotes from Blake. He’s an anarchist. A Romantic. He’s irresponsible. He’s scandalous. I loved him. And I loved his vision, too. I still do.

And I went out to get some room for my grief. Thank God, it was a high sky on Greenbank. Darker than I expected. But the edge of the world was still a long way off. At least as far as Surrey. Under the cloudbank. Sun was in the bank. Streak of salmon below. Salmon trout above soaking into wash-blue. River whirling along so fast that its skin was pulled into wrinkles like silk dragged over the floor. Shot silk. Fresh breeze off the eyot. Sharp as spring frost. Ruffling under the silk-like muscles on a nervous horse…

The fog-bank was turning pink on top like the fluff trimmings on a baby’s quilt. Sky angelica green to mould blue. A few small clouds dawdling up, beige pink, like Sarah’s old powder puffs full of her favourite powder. Air was dusty with it.

Gulley Jimson showed me the way to understand Carel Weight and Stanley Spencer. He made me want to go to art school, just as the Famous Five made me want to outwit crafty foreigners, and Alf Tupper made me want to prove that a working class lad could show the toffs a thing or two. Dreams, escapism and fantasy. Louis Wilde pointed out that I wasn’t good enough for art school, and a good thing too.

What’s all this to do with a poetry cobweb? The link is tenuous, but here it is. Joyce Cary’s Gulley Jimson taught me to feel more intensely. In a particular way, it’s true: to see the world as primarily visual.

Here’s Monet, and Turner, and Sisley and Carel Weight … and it's all done with words, and what’s more, in words you could turn into a poem in a blink. Which is what I realised last week when I read that first sentence of The Horse’s Mouth for the first time in a decade or more. I realised it had gone a lot deeper than I thought, and it had done so because I’d read it again and again in the way I read the ‘rubbish’ that Peter Dickinson defended in the 70s. It sent me back to my notebooks; I wanted to find out that what I suspected was true. That in teaching me a way of seeing Gulley Jimson taught me how to write about it. How about these bits from notebooks of about 10 years ago:

‘… on this hill with no shorthand. Everything very sharply in focus and out of meaning. Tiny white starry flowers, one here, one there. One brown furry caterpillar straddling two bleached plantain stems. Dry flower heads brittle pink. One plump crimson/blush/rose cushion of spaghnum, complex jewelly florets, bright with water drops scattered … Deer slots, random, occasionally, a single one sharp in a cupful of peaty mud … Amber, yellow grasses like blades, flexing.’

This was up on steep moorland near Achnacloich on Skye. And further on:

‘Sky lines recede, one by one, under a slough of driven cloud. Layers and layers.

The near fellside acid sour and bracken brown, tired of cloud, of weight, of wet, of

waiting. A hiddle of oaks in the lee of the ribbon road; black-brittle, acid-burned’

I reckon all that detail of colour and texture is something I learned from a book an art teacher gave me in 1958. Sometime later, other people taught me that you can put line breaks in this sort of stuff and persuade yourself you’re writing poetry. Like this:

a day of edges,

patched plough and fallow; a slanting sun catches

the fold and furl of fields, the tops of dark trees,

their wind-whetted fringes silver and steel

running like cold flames, a cold lambent burning;

the distances are jewelled, wet stones shining precious,

nuggets, faceted and gold-faced; scattered studs

of turquoise fodder bales; the roads a burnished pewter

until a cat-grey cloud bank prowls from the west,

dark and depthless; and whaleback moor-lines blur;

the sunlight’s arch of lemon-silver shrinks.

Rain comes in fronds and veils,in trailed tendrils, skeins,

a ghost of rainbow to the north promises something;

in the background someone is singing:

I spent a long time believing that painting word pictures of landscapes was the same thing as writing poems. Later I spent a lot of time reading and rereading Norman MacCaig, and found out different. You learn from the company you keep. But I’ll argue forever that you need to keep some rough old company to appreciate a fine wine, and that reading rubbish will do you no harm, so long as you read too much of it.

Thanks for your forebearance. It was nice to get that off my chest. Maybe I’ll start writing poems again. Let’s finish with one of my favourite passages from The Horse’s Mouth:

The moon was coming up somewhere, round the corner from the old bow-window, making the trees like fossils in a coalfield, and the houses look like fresh-cut blocks of coal, glittering green and blue and the river banks like two great solid veins of coal left bare, and the river sliding along like heavy oil. It was like a working model of the earth before someone thought of dirt and colours and birds and humans. I liked it so much I wanted to to go out and walk about in it. But of course I knew it wouldn’t be there. You never get the real world as solid as that

It's true. You need the likes of Joan Eardley, and Norman MacCaig to show you the real world, and once you’ve seen it you always will.

The Horse’s Mouth. [1944] Originally published Michael Joseph, subsequently published in Penguin Modern Classics

John Foggin

Thu 22nd Aug 2019 15:41

Thank you for these heartfelt comments, M C Newberry. All power to your pen. And thank you for reminding me that Dickens learned his trade as hack writer, a Parliamentary reporter, a journalist. You remind me that Dickens is another of my comfort blankets...the darker novels, for some reason. Bleak House, Little Dorritt.